Debt-for-nature swaps: Is Ghana mulling over a DFNS?

Kwaku, Accra, Ghana

March 10, 2023

Although Ghana produces a mere 0.14 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG), climate change has detrimental effects on Ghana. Efforts to mitigate or reverse the effects of environmental degradation are absorbing resources and causing fiscal disequilibrium. The government argues that climate change is exacerbating the country’s economic difficulties1. In September 2022, total debt was 75.9 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). The country has since reached a debt restructuring agreement with creditors. Ghana is looking for way to reduce or avoid debt burden. On 24th November 2022, the Minister of Finance, Ken Ofori-Atta revealed that he had approached investors and creditors about debt-for-nature swaps (DFN). He made the announcement during the presentation of the 2023-2024 national budget in the Parliament. The consultations took place during COP 27 in Cairo, Egypt on November 6-18, 2022. He told parliament that he was exploring DFNS as a mechanism to finance climate actions and as a mechanism to reduce national debt.

Prerequisites for a DFN swap

Debt-for-nature swaps redirect government funds, initially earmarked for debt service to environmental initiatives and other development projects such as poverty alleviation and improvement of access to health. The African Development Bank2 states that a well-designed DFNS can help restore fiscal balance. DFNS have embedded debt forgiveness features especially when they results from bilateral or multilateral agreements between the debtor and creditors.

A DFNS requires three prerequisites before it becomes operational. First, it needs a lender who is interested in the fight against the negative effects of climate change. Second, the debtor has to convince creditors that they can allocate the new resources to meaningful climate projects. Third, DFNS have to be part of a transparent public debt restructuring, which does not grant unfair advantages to other creditors. When these three elements are in place, a debtor country may qualify if the level of debt is unsustainable and if the country has exhausted other mechanisms for debt relief.

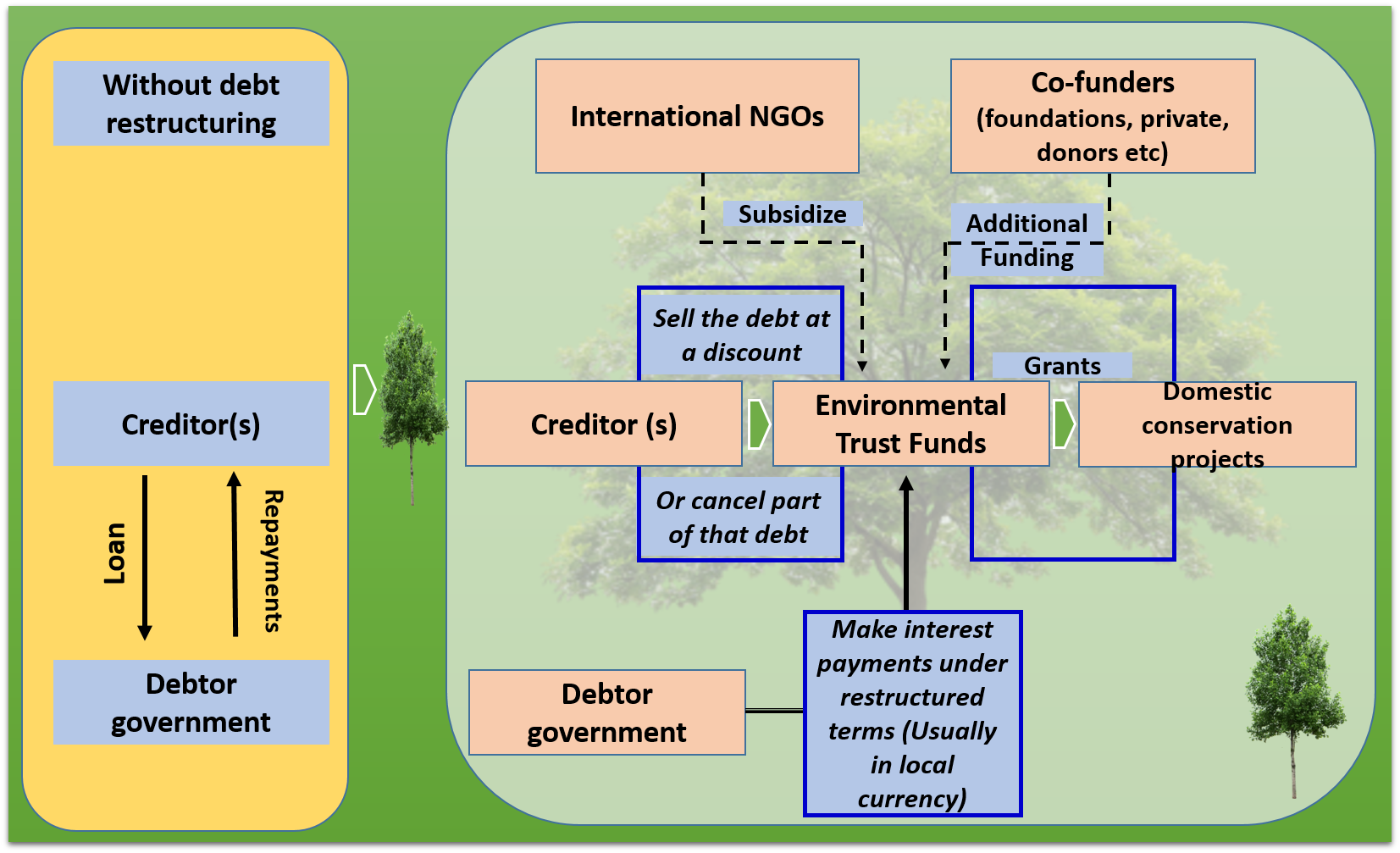

Basic structure of a DFNS

Source: Adapted from Yue and Nedopil, 20213

DFNS in Africa

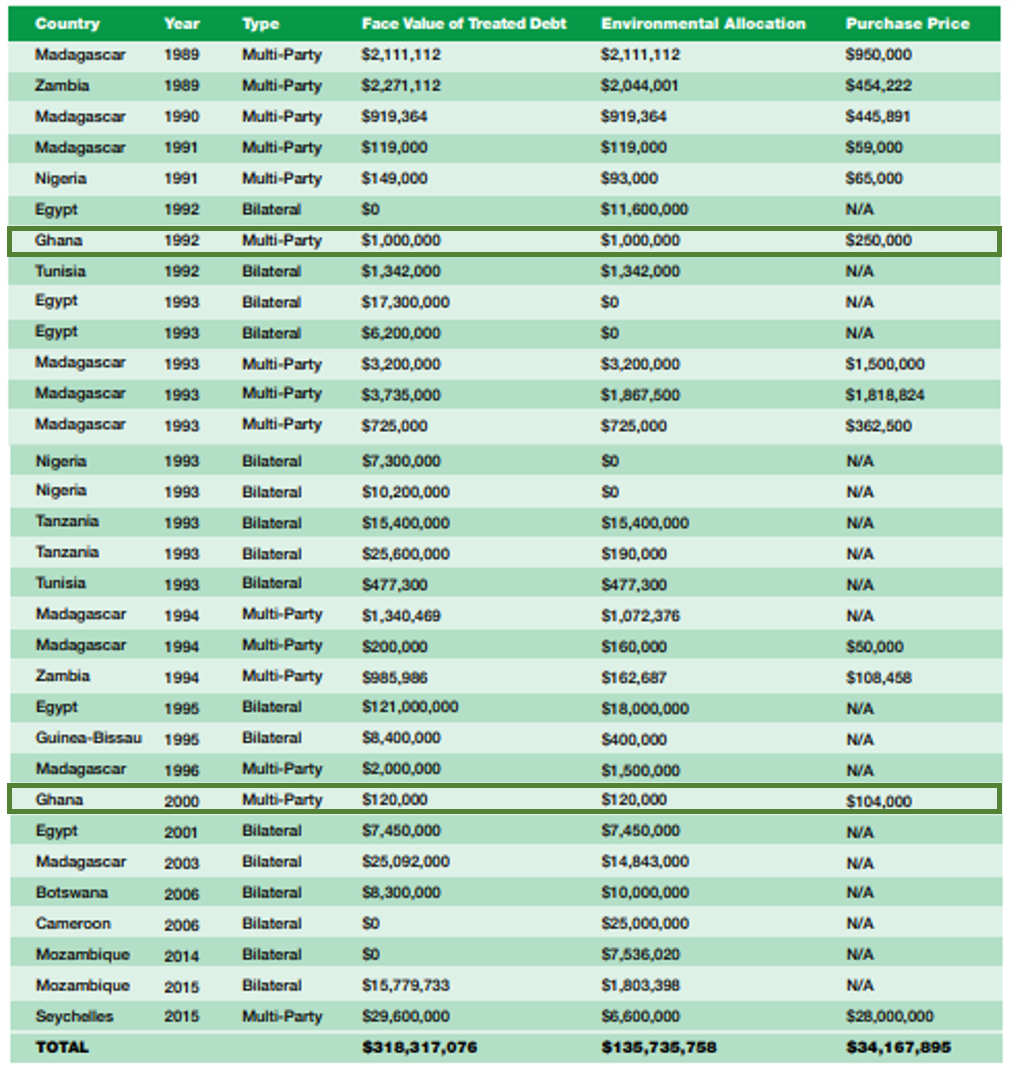

In total, 13 countries, including Madagascar, Nigeria, and Tanzania, have arranged conservation-linked financing. Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia, also benefitted from DFNS. But success has eluded other applicants. Between 1990 and 2020, investors appeared to lose interest in DFNS. But interest resurfaced after the economic devastation of the COVID-19 and the Ukraine-Russia war. Gabon raised US$500 million through DFNS, which lead to a 10 percent reduction of national debt. Cabo Verde and Portugal are working on a similar deal after a pilot study by a London-based think-tank4. Since 1989, this financial instrument has allocated over US$135 million to conservation funding in Africa, according to the African Development Bank.

Historical Debt-for-Nature Swaps in African Countries

Source: African Development Bank, 2022

DFNS in Ghana

Ghana issued the first DFNS in 1992 with the help of five US public and charitable organizations5. The five sponsors teamed up to convert debt worth US$1.00 million into conservation and heritage preservation projects. The beneficiaries were the Kakum National Park and three world heritage monuments on the Cape Coast, including two historic ‟slave castles”. These projects led to the creation of the Ghana Heritage Conservation Trust.

This financing also helped turn the Kakum National Park into the country’s best known eco-tourism landmark. Its canopy walkway has been attracting tourists for the past 30 years. The park, in the Central Region of Ghana, covers an area of 375 square kilometers (145 square meters). Its canopy walkway is 350 meters long and connects seven tree tops, which provide access to the forest. Above the canopy, visitors see tree-tops, rivers, and ravines. From stands 40 meters above ground, visitors discover a splendind carbon-sinking canopy, plants, and wildlife.

In 2000, Conservation International (CI) organized Ghana’s second DFNS. The deal produced a debt relief worth $120,000 for additional projects in the Kakum National Park. While the benefits of DFNS, in the fight climate change, are undeniable, lenders continue to prefer comprehensive debt restructuring, which are typically accompanied by a radical program of economic reform.

Related Articles

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1❩ Patel, S, Klok, E, Steele, P and Camara, IF (2022):After the Paris Agreement, the debt deluge: why lending for climate drives debt distress.

2❩ African Development Bank (2022): Debt-for-Nature-Swaps: Feasibility and Policy Significance in Africa’s Natural Resources Sector. African Natural Resources Management and Investment Centre. 2022.

3❩ Yue and Nedopil (2021): https://greenfdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Yue-2021_Debt%20for%20nature-swaps-BRI-1.pdf

4❩ International Institute for Environment and Development –IIED (2023): Redesigning debt swaps for a more sustainable future

5❩ a- Conservation International (CI),

b- International Council on Monuments and Sites,

c- Midwest Universities Consortium for International Activities (MUCIA),

d- Smithsonian Institution, e- USAID