Remittances and financial inclusion

James Akem, Kumasi, Ghana

January 30, 2024

I n 2011, 22 percent of Ghanaians had access to formal financial services. Over the past decade, access has increased to 41 percent (2014), 58 percent (2017) and 68 percent in 20211. However, despite this progress, over 7 million people (or 32 percent of the population) have no access to formal financial services. Regional disparities and gender gaps persit partly because of the absence of financial service providers in rural areas, language barriers and illiteracy. Data from the Global Findex Database 2021 indicate that 63 percent of women in Ghana have bank accounts in licensed financial institutions. But the gender gap in Ghana has grown significantly in the last five years, from 8 to 11 percent2. The government of Ghana acknowledges that access is still not universal and also that rural areas and low income individuals lag behind3.

Disparities

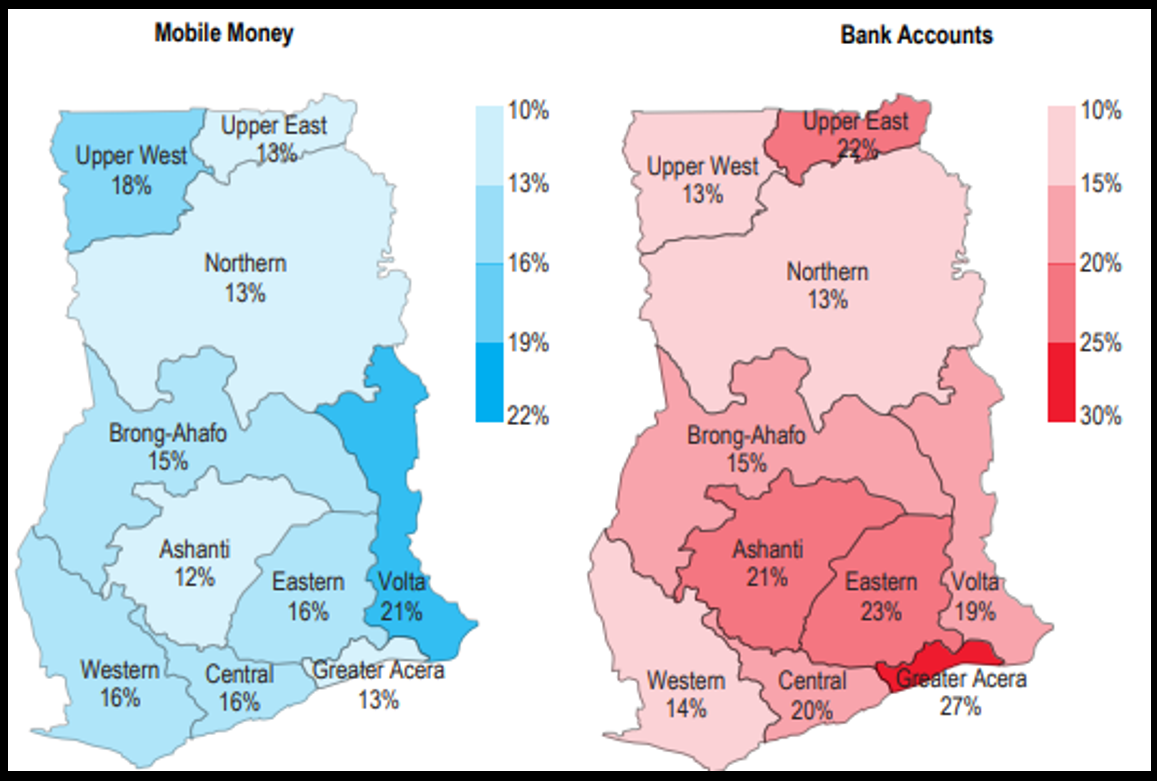

The government estimates, in a strategy document, that ‟access to financial services is heterogeneous across regions and key demographics”4. In the same document, the Ghanaian Ministry of Finance also explains that the five poorest regions (Upper West, Northern, Volta, Upper East, and Brong Ahafo) remain the most financially excluded, despite noticeable growth. Furthermore, rural residents and women, have less access to banks than urban and male counterparts. Rural residents (51 percent of the population) and women (50.7 percent) have to rely on unregulated netrowks, which are not connected to modern digital payment systems5.

Financial Inclusion: regional disparities

Sources: NFIDS (2018–2023)

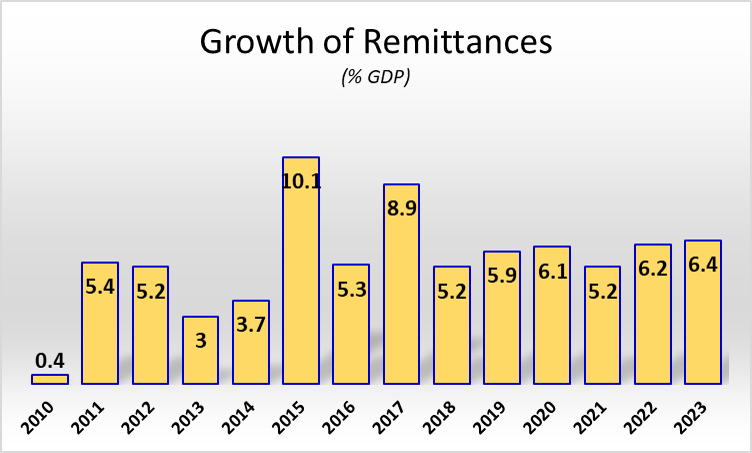

However, mobile money is playing a disruptive role and contributes to the growth of remittances. But since 2020, with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, negative macro-economic developments have increased poverty and further excluded the poor from access to formal financial services. Nevertheless, the use of formal remittances has risen, which as a share of GDP have grown from 3.0 precent in 2013 to 6.4 percent in 2023.

Remittances growth (as percentage of GDP)

Sources: World Bank

Other factors that are influencing the dynamic relationship between remittances and financial inclusion are sociological (gender, age and education, financial literacy), commercial (absence of financial service providers, transparency of cost structure, lack of after service support) and technological (fear of cybercrime, reconnection of those who become disconnected from financial and mobile phone services).

Partnerships for financial inclusion

Since 2017, the government has been working with the World Bank, the United Nations and the CGAP (Consultative Group to Assist the Poor) to foster financial inclusion. In May 2022, the government received financing (US$30 million) from the World Bank to launch the Ghana Financial Sector Development Project (FSDP), The goal of the FSDP is to promote the soundness of and to foster a wider access to financial services. The project will develop a geospatial map of all financial institutions in the country, base on the premises that the distribution of these services has an impact on financial inclusion6.

The Ministry of Finance wants to get a full picture of the financial access points throughout the country to begin to understand how providers can adapt their operational strategies to reach areas that are underserved.

The FSDP builds on previous policies such as the NIFDS, ‟The Digital Financial Strategy” and the ‟Cash-lite Roadmap” which targets the use of technology such as mobile money and other Fintechs to boost access to financial services and also promote an inclusive digital ecosystem. It also builds on the work carried out by the Bank of Ghana which has mapped out and maintains an updated database of all mobile money vendors7.

Remittance risks

Empirical research by the World Bank found that remittances increase financial inclusion when they complement rather than substitute for formal financial services 8. Also, in a seminal 2020 research paper, based on data from 187 countries, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that remittances should not become a substitute for formal financial services. According to this IMF study, when remittances-to-GDP ratio is high, above 13 percent on average, they tend to enhance financial inclusion. However, they can also create high dependence on remittances especially when they become a subsistence means to poor households9.

Researchers from the The IZA Institute of Labor Economics (Bonn, Germany), warned that remittances can produce negative macroeconomic consequences for the recipient country. They reduce labor supply and induce a culture of dependency that inhibits economic growth. Moreover, they can increase the consumption of nontradable goods, raise their prices, appreciate the real exchange rate and decrease exports. The IZA Institute indicates that in this kind of situation, remittances will damage the receiving country’s competitiveness in world markets10.

At the behavioral level, remittances can become become a disincentive to active participation in economic activities for the recipient. Indeed, documented cases of recipients engaging in pointless conspicuous consumption exist. Dependency and binge spending behavior have an insidious impact at the individual level and can feed inflation at the collective level.

Related Articles

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1❩ World Economic Forum (2022): Global Gender Gap Report- Insight Report, July 2022 - https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf

2❩

Ghana Ministry of Finance (2022): Ghana Financial Sector Development Project (GFSDP) - MOF-FSD-CS-047 - https://mofep.gov.gh/adverts/2022-10-10/ghana-financial-sector-development-project-gfsdp-mof-fsd-cs-047

see also

https://mofep.gov.gh/adverts/2022-10-10/ghana-financial-sector-development-project-gfsdp-mof-fsd-cs-047

3❩ Ernest Addison (2022): Speech at the FinTech Award, 2022, Accra Ghana. https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Governors-Remarks-Ghana-FinTech-Awards-2022-27-01-23.pdf

4❩ Ministry of Finance (2018): National Financial Inclusion and Development Strategy (NFIDS) 2018–2023 - https://mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/acts/NFIDs_Report.pdf

5❩ NFIDS ibid.

6❩ Paliament of Ghana (2018): Memorandum - https://ir.parliament.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/1302/MEMORANDUM%20TO%20PARLIAMENT%20BY%20MINISTER%20FOR%20FINANCE%20ON%20A%20PROPOSED%20SDR%2021.4%20MILLION%20CREDIT%20%28EQUIVALENT%20OF%20US%24%2030.0%20MILLION%29%20FROM%20THE%20INTERNATIONAL%20DEVELOPMENT%20ASSOCIATION%20%28IDA%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

7❩ Ministry of Finance Ghana (2023): National Financial Inclusion and Development Strategy 2018–2023 - (NFIDS) https://mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/acts/NFIDs_Report.pdf

8❩ The World Bank Economic Review (2008): A symposium on access to finance, Volume 22, Number 3 https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/807621468161959098/pdf/548650PUB0WB0e10Box349431B01PUBLIC1.pdf

9❩Sami Ben Naceur, Ralph Chami and Mohamed Trabelsi (2020): Do Remittances Enhance Financial Inclusion in LMICs and in Fragile States? - https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/05/22/Do-Remittances-Enhance-Financial-Inclusion-in-LMICs-and-in-Fragile-States-49362#:~:text=At%20low%20levels%20of%20remittances,of%20remittance%2Dto%2DGDP.

10❩ Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes (2014): The good and the bad in remittance flows - IZA World of Labor, November 2014, wol.iza.org - https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/97/pdfs/good-and-bad-in-remittance-flows.pdf