Senegal engulfed in US$7 billion unreported debt scandal

Aziz Ndiaye and Sheikh Said Diallo

Dakar, Senegal

April 1st, 2025

O ver the past three decades, Senegal has been a harbinger of hope in Sub-Saharan Africa; a region devastated by political instability, security issues, and wars. Senegal remains the oldest stable democracy in Africa. The World Bank presents the country as a low middle income country where 36.3 percent of the population still lives below the poverty line. However, with the discovery of vast reserves of oil and gas, the country’s growth prospects have improved. In 2024, Senegal scored 45 (out of 180 countries) Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (TI). TI ranks countries on a scale from zero (‟highly corrupt”) to 100 (‟very clean”

Barely a year after this rating, in February 2025, the Court of Auditors of Senegal (‟Cour des Comptes”) discovered huge undisclosed public debts. In an audit review of public finance, which covered the period 2019-2024, the Court of Auditors found undisclosed public debt of US$7 billion (CFA 4585 billion). In fact, the audit report is littered with dysfunctions, malpractices, and blatant violation of laws, by civil servants and at every level of the public finance decision making. After his swearing in, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye promised a thorough review of public finances and asked the Court of Auditors to carry out this review.

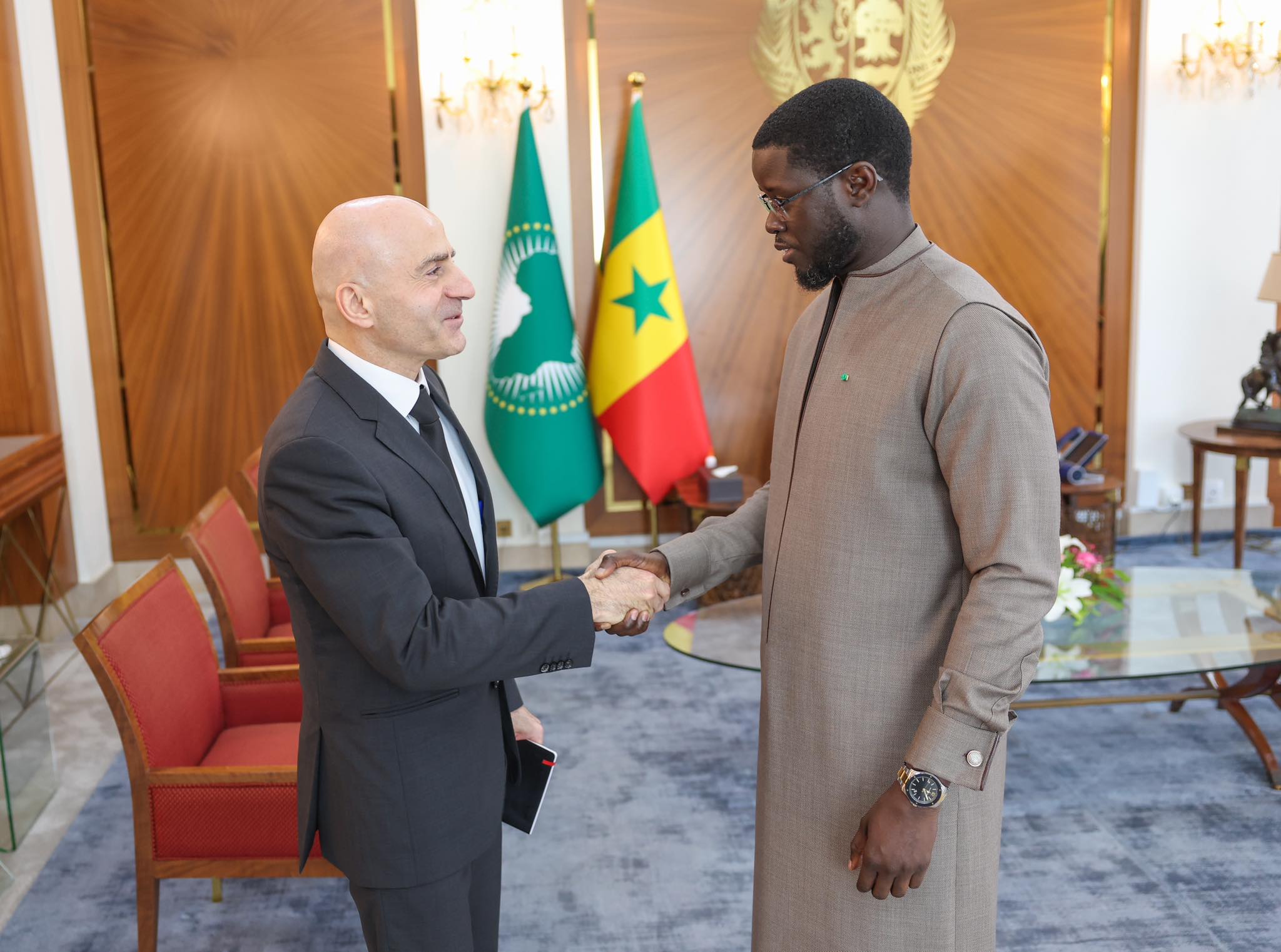

President Bassirou D. Faye and Edward Gemayel (IMF)

Dakar March 25th, 2025 - Photo ©: presidence.sn/

Key Findings of the Court of Auditors

Unauthorized operations and lack of monitoring of state accounts in private banks

The report documents a litany of failures and inappropriate use of public funds. At the centre of these activities is the ministry of finance and budget (MFB) of Senegal and its key departments. The Court of Auditors reported that the MFB has, on several occasions, wired funds from government short-terms accounts for non-authorized and extra-budgetary expenses. Since 2014, US$232.6 million (CFA141 billion) have been languishing in 13 private banks. Private banks which hold the funds have not paid the State any interest on those funds. In fact, the Court of Auditors found that US$34.6 million (CFA21 billion) are missing from the different accounts after consolidation. The public treasury did not properly monitor the accounts.

In addition to taking on cumulative overpriced credits from private banks, the Ministry of finance has converted debts owed to these private banks into expensive ‟I Owe You (IOY)” for a total of US$906 million (CFA 546.7 billion). These transactions have generated additional debts for the State. The Ministry also used ‟debtor substitution” with private banks. In the context of public finance, this type of transaction refers to a situation where one entity (often a government) takes on the debt obligations of another entity (often a private entity or another level of government).

The Courts estimates that these services cost the State of Senegal US$4.1 billion (CFA 2497 billion) between 2019 and 2024. Despite their impact on public finance, ‟the Government's report on the state of public finances does not include bank debt servicing (amortisation, interests, penalties, commission and fees)”. The Court of Auditors also notes that in the absence of monitoring of these unique transations, by the services of the Ministry of Finance and Budget, ‟the completeness and extent of these debts cannot be established with accuracy”.

Irregularities in public revenues and expenses

State revenues from customs are not fully recovered, sometimes even when they are known, recorded and traceable. On March 31st, 2024, the Court of Auditors estimated that the government has not recovered a portion of revenues worth US$1.10 billion (CFA 669,9 milliards) due to negligence and omissions. The auditors stressed that despite their importance, ‟customs duties are not subject to centralized administrative and accounting monitoring, unlike registered direct taxes”. They conclude that these costly omissions of customs receivables ‟impairs the accuracy of data relating to outstanding amounts and provides an incomplete picture of their situation”.

Other irregulaties related to accounting practices and procedures. Within the ministry of finance, departments in charge of revenues have been carrying forward past revenues into every new fiscal year. These irregular recognition of revenues in accounting terms artificially boosted revenues, this malpractice produced a false reduction of annual fiscal deficit. For example, without these irregular recognitions, fiscal deficit increased by 0,46 percent of the GDP (2022) et 0,27 percent (2023),

The handling of public expenses also shows dysfunctions and malpractices. The Directorate in charge of budget, within the ministry of finance, authorized inappropriate transfers of funds to different entities, but without evidence of service delivery to the state. The Court of Auditors notes that the Directorate has no statutory powers to undertake such financial operations, outside of its own department or on behalf of the state of Senegal. In one instance, the Directorate even used US$503.3 million (CFA 305.9 billion) of state funds to repay bank debts without following due process. In sum, the Court of Auditors reports that between 2019 and 2024, ‟Non-Personalized State Services (SNPE)” or entities without statutory functions and habilitations, benefited from budgetary transfers. ‟These transfers totaled US$4.2 billion (CFA2562.17 billion), representing 28.06 percent of the overall transfers from the general budget”.

Missing funds from multilateral and bilateral donors

The Court of Auditors reviewed financing provided by seven multilateral agencies for socio-economic programs in Senegal. Agencies included in this review are the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the Islamic Development Bank and the French Agency for International Development. This review also covered financing from the West African Development Bank (BOAD), Chine and USAID. The Court of Auditors found that ‟the difference between the financial report produced by the Department of the Paymaster General of the Ministry of finance and that appearing in the Government's report ” was US$237.2 million (CFA143,98 billion). This conclusion came after an analysis of operations from two banks that hosted the donors’ funds (Société Générale et Standard Chartered Bank). In this specific case, contradictory and conflicting figures have appeared at every level, including budgeting, drawdowns and use of proceeds of funds.

The Court of Auditors points to the fact that unlike donors, Senegal does not have a reliable automated system to record and track data on, and manage external contributions from multilateral, bilateral and other donors. After this finding, the ministry of finance announced plans to secure donors’ financial data‟through a platform dedicated to the management and monitoring of external financial resources”. Senegalese authorities also announced that this platform will be operational before the end of fiscal year 2025..

Under-reported public debt

Between 2019 and 2024, Senegal’s funding needs for infrastructure projects and social programs doubled from US$2.00 billion (CFA1227,68 billion) to US$4.3 billion (CFA2642,70 billion). During the five-year period, Senegal borrowed more funds that it had projected. Bilateral donors, domestic banks and external commercial banks provided loans and lines of credit. Borrowings from international commercial banks included non-concessional loans. Senegal also issued short-terms instruments (TBills) and medium-term bonds at the Regional Stock Exchange (BRVM) in Abidjan.

The authorities also tapped Islamic finance. Senegal put its full credit worthiness and assets in an Islamic Sukuk bond issued by the state-owned Société de Gestion et d’Exploitation du Patrimoine de l’État (SOGEPA). In June 2022, Senegal, through SOGEPA SN, issued a US$525.4 million (CFA 330 billion) three-tranche Sukuk Ijarah, making it the country’s third Sukuk offering in six years. But, the ministry of finance used a part of the proceeds; US$187.8 million (CFA114,4 milliards) in transactions outside of the formal legal treasury procedures. In its final recommendations, the Court of Auditors has asked the Ministry of finance to return these funds to the national treasury.

Cases of borrowing by the ministry of finance, which took place outside of the formal budgetary and public finance procedures, have emerged. In 2022, the ministry of finance borrowed US$149.8 million (CFA91 billion) from a domestic private bank; International Business (IB), on behalf of the State of Senegal without parliamentary approval. In the terms, Senegal agreed to repay the borrowing in 2026 with interests and initial loan totaling US$173 million (CFA105 billion). This loan was not reported and in 2023, the Court of Auditors found even more discrepancies between Government Treasury reports and the public finance law 2023 (or ‟Projet de loi de règlement” in French). These under-reported of debts lowered Senegal fiscal deficit between 2019 (3.9 percent) and 2023 (4.9 percent).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) visits Senegal

On March 26th, 2025, a team from the IMF visited Senegal to review findings of the Court of Auditors. The team met Senegalese authorities and other stakeholders. In the readout from these meetings the IMF team acknowledged and confirmed ‟significant under-reporting of fiscal deficits and public debt”. According to the IMF, at the of end-2023, the government revised fiscal deficit by 5.6 percentage points of GDP, and central government debt from 74.4 to 99.7 percent of GDP. Consequently, at the end of 2024, central government debt increased with preliminary estimated placing it at ‟105.7 percent of GDP” while deficit rose to 11.7 percent. The Fund concluded that ‟these revisions primarily reflect previously undisclosed liabilities, including hidden loans amounting to 25.3 percentage points of GDP”.

Financial markets sanction Senegal

The state of public finances in Senegal has triggered a chain reaction in financial markets, which began with a rating downgrade by Moody’s at the end of 2024. Moody’s downgraded Senegal’s long-term issuer and foreign-currency senior unsecured ratings down to B3 from B1 and changed the outlook to negative. This means that Senegal is just one step above a C-level rating where countries are susceptible to default. Moody’s said that Senegal is in ‟a very weak fiscal and debt position (which) will complicate fiscal consolidation efforts”.

Meanwhile, at the London Stock Exchange, after the IMF’s visit, yields on Senegal’s Eurobond maturing in 2048 declined for a third consecutive day since March 22nd 2025, by 0.4 percent to 66.55 cents on the dollar. Similarly, Senegal's notes maturing in 2031 also lost 0.4 percent to 84.96 cents on the dollar, according to Bloomberg Markets. With these cascading bad news, investors in Eurobonds expect Senegal to pay more to cover their risk. However, Prime Minister Ousman Sonko has stressed that his government can turn the situation around. The authorities forecast a growth rate of 6.5 percent in 2025, with bullish prospects on oil and gas reserves and a promise of vigorous reforms in 2026.

Related Articles