Ghana in search of a growth trajectory

Clovis Asamoah, Accra, Ghana

April 12, 2024

S ince independence from Britain in 1957, Ghana has pursued a two-pronged economic growth strategy. The import substitution model has been an enduring corner stone of the country's economic policy throughout the decades. Through this approach, the country aspires to achieve economic development by trading with other nations. At the same time, this model premises a reduction of import through the development of domestic manufacturing and home-grown industrial capacity. A key goal is therefore, to reverse Ghana's dependence on import, notably of basic goods, industrial components, manufacturing input and even modern technology.

The infrastructure-led growth is the second prominent model in the economic development blueprint of Ghana. This model seeks to remove constraints and bottlenecks around economic activities. Ghana appears to be in accord with multilateral development institutions who argue that inadequate infrastructure (lack of electricity, limited access to clean water, obsolete telecommunication network and transport) hinders economic development. But, in recent years, a review of past infrastructure investments show that Ghana’s infrastructure-led growth experiment is faltering because of the massive debt it has incurred.

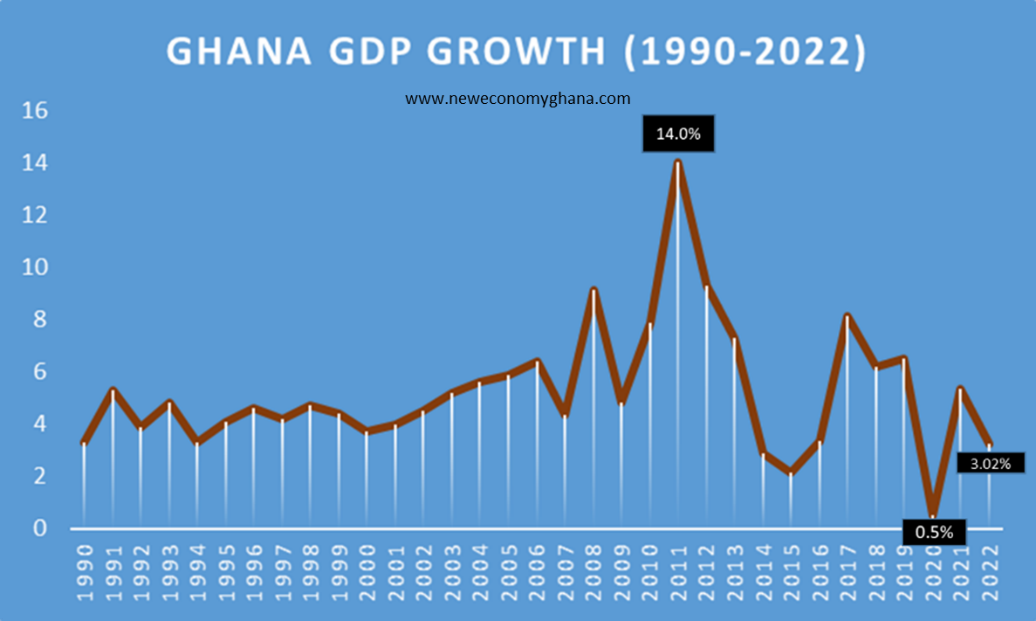

Nevertheless, despite their shorcomings, these two models have served Ghana well, especially when they propelled the country to the status of middle income country in 2011. But, recent external shocks have highlighted their risks and limits, forcing Ghana to embark on a new growth trajectory. The pillars of the new strategies are trade, investment, technology, labor, and productivity.

Ghana Growth Story

Source: Ghana Statistical Service

Trade

Ghana’s exports has been growing in value and volume, generating foreign exchange earnings, while boosting the gross domestic product (GDP). But, the country exports raw unprocessed natural resources with limited or no added value. This is the case with hydrocarbons, mining, and agricultural crops. Export has the potential to induce economic growth1 but its real positive effect depends on conditions in the international markets. On a scale, dependence on commodities increases the country’s vulnerability to external shifts in demand. On the other hand, dependence on a narrow export destination increases vulnerability to external economic cycles. Together, these conditions expose Ghana to externalities on which authorities have little control2. In its new growth model the country is seeking to restore an equilibrium and also navigate complex uncertainties and contagions.

Dependence on import, on the other hand, inhibits domestic industrialization and manufacturing. It also distorts macroeconomic fundamentals including fiscal balance, reserves, inflation and currency. Ghanaian authorities acknowledge the impact of these distortions. According to former minister of finance, Ken Ofori-Atta, ‟Ghana’s heavy dependence on imports exerts pressure on the Cedi, thus, creating an unfavorable balance of payments position”. During the presentation of the 2023 budget, on 24th November 2022, the minister also recognized that ‟growth has stagnated and even declined because of this dependence”. Ghana is addressing these shortcoming by calibrating its approach through a new vision, that recasts various past development models including import substitution. In ‟Vision 2057: Long-Term National Development Perspective Framework”, the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) envisons ‟a prosperous, self-reliant, and resilient nation with a strong emphasis on economic growth, social development, and environmental sustainability”. But ‟Vision 2057” is not a plan, rather it charts ‟a development path”3.

Investments

Ghana continues to invest in infrastructure to create a fluid business environment. Investments in transport, energy supply, health, and education can boost economic activities. The Ghana National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) outlined infrastructure investments for the period 2018-2047 in an official policy document. Under the Ghana Infrastructure Plan (GIP) 2018-2047, the Commission expects Ghana’s economic output and GDP to increase from US$73.77 billion in 2022 to US$3.6 trillion in 2057. Ghana will target an average national income (or per capita gross national income - GNI) of US$60,000 (US$22,000 in today’s price).

Over a period of 30 years, Ghana will need US$2.3 billion per annum (GH₵$1.1 trillion) to realize these infrastructure ambitions. The funds will go to priority sectors. Housing will receive (62.2 percent), transportation (23 percent), and energy 8 percent. Other priority areas include water and drainage (1 percent), ICT (1 percent) and waste management (1 percent). The State aims to recoup the initial capital expenditure through taxes and also revenues from public private partnerships, joint ventures and various forms of management concessions.

Ghana needs an innovative approach to avoid an increase in public debt. In 2023, unstainable public debt plunged Ghana into a severe debt crisis. This time around, the government says it wants to avoid debt by encouraging the participation of the private sector.

Labor, productivity, and technology

Ghana is counting on innovation and technology to improve productivity. With that goal in view, the government is investing in infrastructure, transparent business climate and improved work conditions. Ghana has land, plenty of natural resources and a young workfore. But, it lacks technology and capital. Together, these two factors of production have the potential to increment output.

The labor force of Ghana is in constant mutation as it seeks to respond to economic changes. But informality is rampant in the economy. Agriculture, services, transport and extractives have high degrees of informal activities. The World Bank’s estimates that the informal sector accounts for 70 percent of current jobs, while over 65 percent of formal jobs are classified as periodic and ‟vulnerable employment”. This means that the state cannot account for a key component of the labor force4. Authorities say technology will help shrink the size of the informal economy5 at a time when Ghana needs mid-skilled and high-skilled workforce to drive productivity. Investing in digital skills, in primary, secondary, and tertiary education is a prerequisite for this transformation.This will help young Ghanaians to transition from low to skilled jobs and match skills with labor demand.

Time for domestic demand–led growth model?

High-income countries have a strong domestic market for their product and services. After satisfying domestic demand, they channel extra output to export. In comparison, Ghana’s past economic and growth models carry a paradox.

Specifically, the country supplies the world with cocoa, but transforms less than 30 percent at home. It then imports finished chocolates from outside. Similarly, Ghana is Africa’s first gold producer, but compared to its peers, the Bank of Ghana has a low gold reserve. In 2020, South Africa, second producer of gold after Ghana had 125 tons of gold reserves, compared Ghana with 34.7 metric tons. This economic paradox replicates itself in other sectors. In October 2022, the Ghana Food and Drug Authority (FDA) found that 79 percent of consumer items in supermarkets shelves were imported products. Ghana made only 21 percent of the consumer items found on supermarket shelves.

Given the shortcomings of current growth models, discussions are emerging around a new development paradigm that will be driven by domestic demand-led growth6. Harvard Economist Dani Rodrik has argued that a domestic market is a resilient and reliable engine of sustainable growth. He postulated that, in emerging markets, high growth rates stem from domestic demand7. Kenyan Economist David Ndii8 agrees. His research found that the domestic demand–led growth model is scalable. Specifically, Ndii has identified agriculture-led growth as an effective engine for economic progress in Sub-Saharan Africa and as an alternative to past models.

Related Articles

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1❩ The Economist Newspaper. (2006): Guide to economic indicators, making sense of economics, page 137

2❩ Thomas I. Palley (2012): The Rise and Fall of Export-led Growth

3❩ NDPC (): Vision 2057: Long-Term National Development Perspective Framework - https://www.ndpc.gov.gh/media/Long-Term_National_Development_Perspective_Framework_Vision_2057.pdf

4❩ Budget 2020

5❩ Food and Drugs Authority – FDA (2022): Policy Brief, Vol: 01, Issue: 01, October 2022

6❩ Thomas I. Palley (2002): A new development paradigm domestic demand-led growth https://fpif.org/a_new_development_paradigm_domestic_demand-led_growth/

7❩ D. Rodrik. Et al (2003): In Search of Prosperity: Analytic Narratives on Economic Growth, edited by D. Rodrik. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

8❩ David Ndii (2022): Africa’s Infrastructure-Led Growth Experiment Is Faltering. It Is Time to Focus on Agriculture., https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/12/20/africa-s-infrastructure-led-growth-experiment-is-faltering.-it-is-time-to-focus-on-agriculture-pub-88662